17 Feb The Cuban Lesson – Ask, Learn, Lead

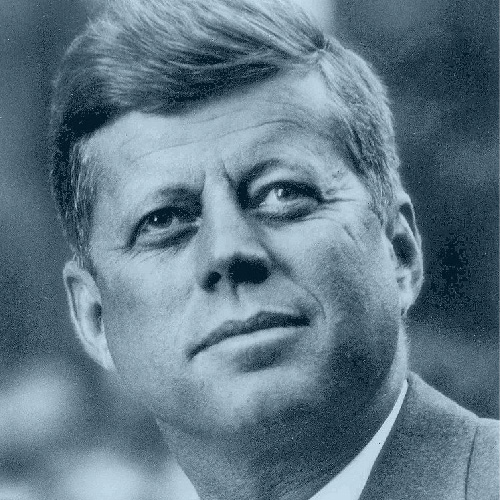

“Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world, ask not what America will do for you, but what, together, we can do for the freedom of man.”

With these stirring words, John Fitzgerald Kennedy became the 35th man to take office as President of the USA on 20 January 1961, and by one of the narrowest margins on record. In the next three years, he gained the respect of many for his coolness under pressure, his eloquence and inspirational speeches, and his compassion and willingness to fight for new initiatives to assist the poor, the elderly and the disadvantaged.

Kennedy’s death at the hands of an assassin on 22 November 1963 meant he did not live to see the fulfilment of many of his “New Frontiers” domestic policy initiatives and his search for new frontiers in space, but his optimism and his passionate belief that people could solve their common problems by placing their country’s interests ahead of personal gain set America on a sustained growth path in the aftermath of the Second World War, and marked a turning point in the Cold War. His leadership, personality and courage remain a lasting legacy to the US and the world.

Speaking at a forum marking the 40th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which had brought the world to the brink of nuclear catastrophe, Kennedy’s special counsel and advisor, Theodore Sorensen commented:

“…what I learned about presidential decision-making I learned at the feet of a pretty good teacher, John F. Kennedy. And I learned from him not to make a decision of life or death, war or peace, without having all the information, and having the opportunity to review all the options” (Sorensen, “On the Brink”, 20 October 2002). Ironically, Kennedy himself had learned this lesson following one of his biggest errors in judgment – one which would haunt the rest of his administration, and which prompted him to reflect: “How could I have been so stupid?”

The Bay of Pigs Debacle

At issue was a plan, conceived by the CIA during the Eisenhower years, to arm and train Cuban exiles to depose Fidel Castro. On 17 April 1961 over 1,400 invaders of the so-called Brigade 2506 landed at Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) in what quickly became a rout. Lacking air and naval artillery support, sufficient ammunition and an escape route, approximately 100 were killed and 1,200 captured by the waiting and highly organised Cuban troops, who had been tipped off by advance media reports. Hopes for a local uprising never materialised, and Castro was driven further into the arms of the Soviet Union, who offered to protect the island against future American invasions.

Multiple factors contributed to the Bay of Pigs debacle, but underpinning them all was a concept subsequently defined as “group think” – flawed group dynamics that can allow bad ideas to go unchallenged. Group think usually leads to faulty decisions because it is the result of a desire for conformity and concurrence within the leadership group, at the expense of critical and objective thinking. The lack of dialogue within the military leadership meant the need for naval artillery support was never discussed and the conditions on the ground were never assessed.

The same lack of “dissenting” ideas and objective scrutiny occurred at the Cabinet level too. At one crucial meeting Kennedy asked each member to vote for or against the invasion – each, that is, except for his advisor, Arthur Schlesinger, who had already expressed serious objections about the plan in a number of private memoranda to Kennedy. These concerns were never voiced openly, and many Cabinet members simply assumed others were in favour. And so the debacle was permitted to occur.

“In the months after the Bay of Pigs I bitterly reproached myself for having kept so silent during those crucial discussions in the cabinet room,” Schlesinger subsequently confessed. “I can only explain my failure to do more than raise a few timid questions by reporting that one’s impulse to blow the whistle on this nonsense was simply undone by our inability to challenge one another and ask questions.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis

For all the embarrassment and challenges brought about by the failed invasion, Kennedy learned the lesson and changed his decision-making style to encourage questions, dissent and critical evaluation. A year later it was put to the test.

On 16 October 1962 Kennedy was informed that a US spy plane had uncovered the secret construction of a Soviet missile site on Cuba. His Chiefs of Staff recommended an air strike against the missile sites and other potentially hostile targets. It was a tough choice: attack Cuba and risk nuclear war with the USSR, or do nothing and expose America to a direct nuclear threat from a range which made pre-emptive strikes all but impossible.

Unbeknown to the Americans, Soviet commanders on the ground in Cuba already possessed an ample supply of tactical nuclear weapons and had the authority to use them in the event of an American attack. Fortunately, the youngest-ever incumbent of the White House, himself a decorated war hero, stood up to his military leaders and rather than engage in a shooting war, he sought a solution that would minimise the possibility of war. It was a time for cool heads, persistent yet decisive leadership, and, above all, crystal clear communication.

He imposed a quarantine zone around Cuba, warning the international community that no interference would be tolerated in this part of the world and that any ship attempting to enter Cuban waters would be stopped and searched. But Kennedy also knew that communications were essential if the missiles were to be removed without a large loss of life on all sides. He immediately opened active and concerted negotiations with his Soviet counterpart, doing everything possible to ensure Chairman Nikita Khrushchev would not feel himself driven into a corner where his only choices were humiliation or escalation.

For thirteen days in October 1962 the two superpowers hovered on the brink of nuclear catastrophe, its leaders trying desperately to avoid the one bad decision, the one communication faux pas that could have precipitated World War Three. Kennedy and Khrushchev opened a hotline between the White House and Kremlin to keep the channels of communication open.

On 28 October the two nations agreed that all Soviet missiles would be removed from Cuba, in exchange for a US guarantee not to invade Cuba and a secret promise to dismantle the US missile base in Turkey. War had been averted, and Kennedy’s decision vindicated.

The Aftermath of Cuba

As he had learned from the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy reflected deeply on the implications of the second Cuban incident. It reaffirmed his believe that standing firm on principle was necessary (witness his strong stand in Berlin in 1963), but that lasting peace required re-examining his own values and perceptions, and reaching out to others in a spirit of cooperation. Consequently, he invited the Soviets to collaborate on space exploration projects and set the example in limiting nuclear tests.

In one of his most famous and eloquent speeches at American University on 10 June 1963 he appealed to the public, as much as to corporate and world leaders to focus on resolving conflict and differences through peaceful means built on a foundation of dialogue and example. “The quality and spirit of our own society must justify and support our efforts abroad. We must show it in the dedication of our own lives,” he exhorted.

“So let us persevere. Peace need not be impracticable, and war need not be inevitable. By defining our goal more clearly, by making it seem more manageable and less remote, we can help all peoples to see it, to draw hope from it, and to move irresistibly toward it. … So, let us not be blind to our differences–but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

One cannot help but ask what more Kennedy would have done for America and the world had his life not been cut short. But his legacy endures, and encourages business and project leaders to continually ask questions, to learn from mistakes, and to focus attention on an optimistic future in which differences are resolved for the common good.

Ask not what you can get, but what you can give.

No Comments